Sophomore uses perfect pitch for piano

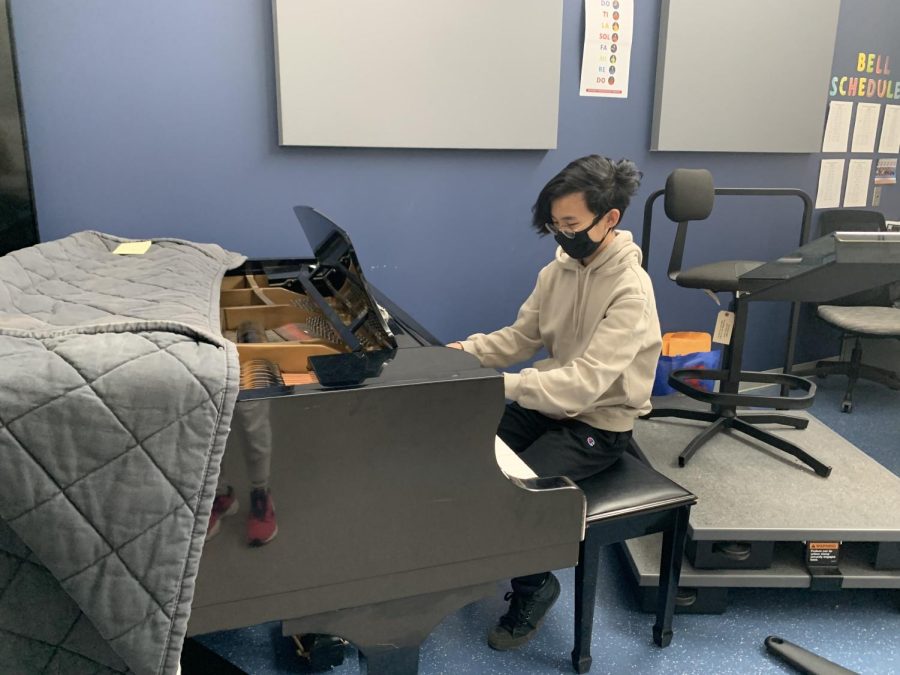

Kondo rehearses a song.

When sophomore Fuma Kondo moved across the world as a young child, he couldn’t speak English, let alone play the piano. His parents enrolled him in piano lessons, hoping to simultaneously teach him English and the art of music.

The family soon met Philip Nagashima, who became Kondo’s piano teacher for the next twelve years and beyond. Through difficult times, the instructor and student have stayed together, even as Nagashima moved back to Taiwan and Kondo stayed in the US.

“He [Kondo] came to me right after his family moved to Akron from Japan. At the time he couldn’t speak English and hardly knew how to play the piano. As he learned to speak the language, he simultaneously learned how to play and express himself through the piano,” Nagashima said.

At age sixteen, Kondo plays high-level pieces and hopes to one day write his own music with the help of his perfect pitch.

Through their many years together, Kondo and Nagashima have bonded, each gaining a distinguished respect for the other. Nagashima described Kondo’s growth over the years.

“He was not an ordinary kid; he is quite a unique individual. Just like his first name, ‘Fuma,’ two Japanese characters ‘wind’ and “horse,” he was my wild-horse like student—not easy to tame or not easy to teach at the beginning. But I saw his potential: he has perfect pitch, the ability to memorize complex patterns of notes, good natural rhythm and a desire to play fast and with excitement,” Nagashima said.

Although his immense skills in piano have provided him many opportunities, Kondo is especially grateful for the bonus skills achieved through his time with the instrument.

“I think one of the best things I’ve learned from piano is learning how to practice. Having a teacher that can teach you how to be a good student and understand what makes a good student makes you better at other skills. Knowing how to practice, knowing how to improve is an incredible part of not just instruments, but life in general,” Kondo said.

Kondo emphasized the importance of practice and patience, sharing some of the skills he has acquired.

“It’s all about patience. It’s about being self critical. If you have the mindset that you can always improve on something and you understand that your self criticisms are valid and are reasonable, then I think that you are good,” Kondo said.

Although many people associate high-level skills with extensive practice, Kondo believes that a skill and learning to practice that skill are completely different aspects.

“I think practicing piano is a whole different skill set than just playing piano. I think practicing is incredibly important and is one of the most valuable things I’ve gotten out of piano, just knowing how to practice, and not just in piano, but other skills in general. I know how to practice more efficiently and be self-critical,” Kondo said.

Similarly, Kondo emphasized the key to his success was an emphasis on quality over quantity; practicing well for twenty minutes is more beneficial than messing around for thirty minutes.

“[It’s] a little embarrassing, but I practice ten to twenty minutes max every day, but I’ve continued to play every single day for the whole entire sixteen years, so it’s mostly just consistency,” Kondo said.

To play piano at an advanced level, one must overcome the temptations of slipping into bad habits.

“There are a lot of aspects to practicing. First of all, you have to be patient. When it comes to something like piano, you have to realize that playing slower can be the faster way of learning than playing fast. If you play fast, you’re going to develop bad habits over time, and it’s going to be harder to fix those and be able to play perfectly in that spot,” Kondo said.

Kondo’s piano teacher agreed, emphasizing that even with immense talent, proper training is the key to success.

“Advanced-level pieces, like he just performed at the school [for the variety show], didn’t come naturally as one might think. It took many years of proper training,” Nagashima said.

Although Nagashima and Kondo started their practices in Ohio, Nagashima has since then moved back to Taiwan. In order to still continue their lessons, the pair has switched over to virtual learning.

“I just do it virtually. Like two years ago, I went to his house and he had two grand pianos, which is insane and I played there. Virtually, it’s not much different. I’d imagine it would be a lot harder for younger piano students, but I think I’ve learned to have more patience,” Kondo said.

RHS senior Camden Moore also takes lessons virtually from Nagashima. Moore talked about how the format has changed after switching to online lessons.

“It’s a lot harder now since obviously we don’t have that person-on-person mentoring, so a lot of what we do is just online lessons, which honestly are a nightmare since the connection is terrible since I’m calling from Ohio and he is calling from Taiwan. Most of the time, he’ll say something like ‘Camden, play C’ but it doesn’t come out as ‘Camden, play C,’ it just comes out as ‘ah-oh-beep,’” Moore said.

Moore continued, explaining what lessons were like originally.

“When he [Nagashima] lived in Ohio, he was originally a professor at the University of Akron, and he did full time piano teaching. He also had a brother that did a similar thing, but he also had to leave for Taiwan for complicated reasons,” Moore said.

When Moore and Kondo did piano lessons in person, usually one followed the other. Since they were at a similar level, Nagashima would ask each student to listen to the other.

“I’d always walk into him doing a lesson with my teacher and sometimes he would make Fuma stay after just to watch me play since he thought he could pick something up from me based off of the way I played,” Moore said.

Aside from piano, Kondo also participates in cross country. Running gives him a chance to clear his thoughts and focus on his music.

“I do cross country because it’s fun, and I think that running is kind of a refresh of my mind, and the only thing I think of when I’m running is music. It would usually be the songs I’m playing right now, I have it looped in my head. It helps me to memorize and I think of ways, like maybe I could play like this when I get home, it’s just like a refresh,” Kondo said.

When Kondo is playing music, he repeats it in his head rather than playing it through a device.

“I actually dislike listening to music. I just kind of play it in my head. Every single time I listen to music on my headphones, it kind of interrupts what I’m thinking, and I already have horrible ears,” Kondo said.

Kondo partially accredits his dislike of listening to pre-recorded music to his perfect pitch.

“I have perfect pitch, so I can comprehend notes really well, but my hearing is awful and it kind of interferes with my thinking,” Kondo said.

Perfect, or absolute, pitch refers to the ability to recall a specific note upon hearing it.

Kondo does not remember when he first knew he had perfect pitch, but knows that it has helped him through his learning of new piano pieces.

“I don’t know when I got it, but it just kind of happened. It helps with, usually when I’m starting a new piece, I listen to it on loop twice, three times and I get a general understanding of how the song goes and it just kind of loops in my head the rest of the day,” Kondo said.

Although the idea of perfect pitch seems ideal for a piano enthusiast, Kondo expressed that it can also be frustrating.

“Perfect pitch is sometimes annoying because every single time you hear a note, you can’t not think about what note it is. It fills up your head with what the notes are, and it’s hard to concentrate. I have a very, very hard time listening to the lyrics of any song,” Kondo said.

Revere band director Dr. Darren Lebeau has taught at Revere for over twenty years and has recently earned a PhD in music education. Through his education, Lebeau has spent time studying perfect/absolute pitch. Lebeau explained how the concept of absolute pitch can be confusing and is still greatly debated.

“There is some debate about perfect pitch. It’s more like absolute pitch. There is a lot of research about the terms used and how one attains perfect/absolute pitch. Can you be trained, is it a cultural trait and so forth?” Lebeau said.

In Kondo’s case, his perfect pitch mostly applies to piano and violin.

“I think my perfect pitch isn’t that good because it’s specialized towards piano and violin; anything else is very difficult for me to comprehend. Violin is very clear so it is easy to understand, but everything else is hard,” Kondo said.

Although his perfect pitch applies to violin, Kondo doesn’t currently play the instrument.

“I did the clarinet in band; it didn’t work. I tried violin in orchestra; it also didn’t work. So I’m just sticking with piano,” Kondo said.

In late January, Kondo performed at the Variety Show, which was one of his biggest performances yet.

“I don’t perform that often, especially in a concert [setting]. Usually I work towards performing at the concerts that [my teacher] facilitates, so it’s usually in an audience of around fifty people. I think the variety show was one of the largest audiences I’ve played in front of,” Kondo said.

Although the piano offers the versatility of playing essentially every genre, Kondo focuses on classical music.

“I focus completely on classical music. I don’t really play anything else. And also solos, I don’t do much ensemble stuff or play in orchestras. It doesn’t suit me very well, and I’m just not good at it. And if I’m being honest, it just kind of bores me. I’m sure it’s fun for some people, but it’s boring for me,” Kondo said.

When playing classical music, Kondo loves to cover Chopin songs.

“I’m currently completely in love with Chopin. Chopin is my favorite composer, and then Haydn,” Kondo said.

Inspired by Chopin and a fellow band who performed at the variety show, Kondo has been trying to write his own music.

“I’ve been trying, but it’s a lot harder [than I thought]. I think my music theory skills are definitely not on par with where they should be. I definitely need to work on it. I’d love to compose music. After listening to stuff like Cameron Weir’s band at the Variety Show, it was super inspirational,” Kondo said.

Through the nine plus years that Nagashami has taught Kondo, he has witnessed Kondo’s growth.

“As Fuma grew up, he found his identity in playing the piano. Music can transcend words, and he has achieved the level to make this happen,” Nagashima said.

Nagashima is proud of Kondo and his impressive growth and talent.

“I want to emphasize again, to have the skill he has now is not just by his talent – he worked hard to achieve it. This discipline and the work ethic he has acquired through studying with me will help him to excel in whatever else he wants to do in the future,” Nagashima said.

Continuing his path of growth, Kondo hopes to one day compose his own music.